A Debate of Great Capes: Which is Most Fierce?

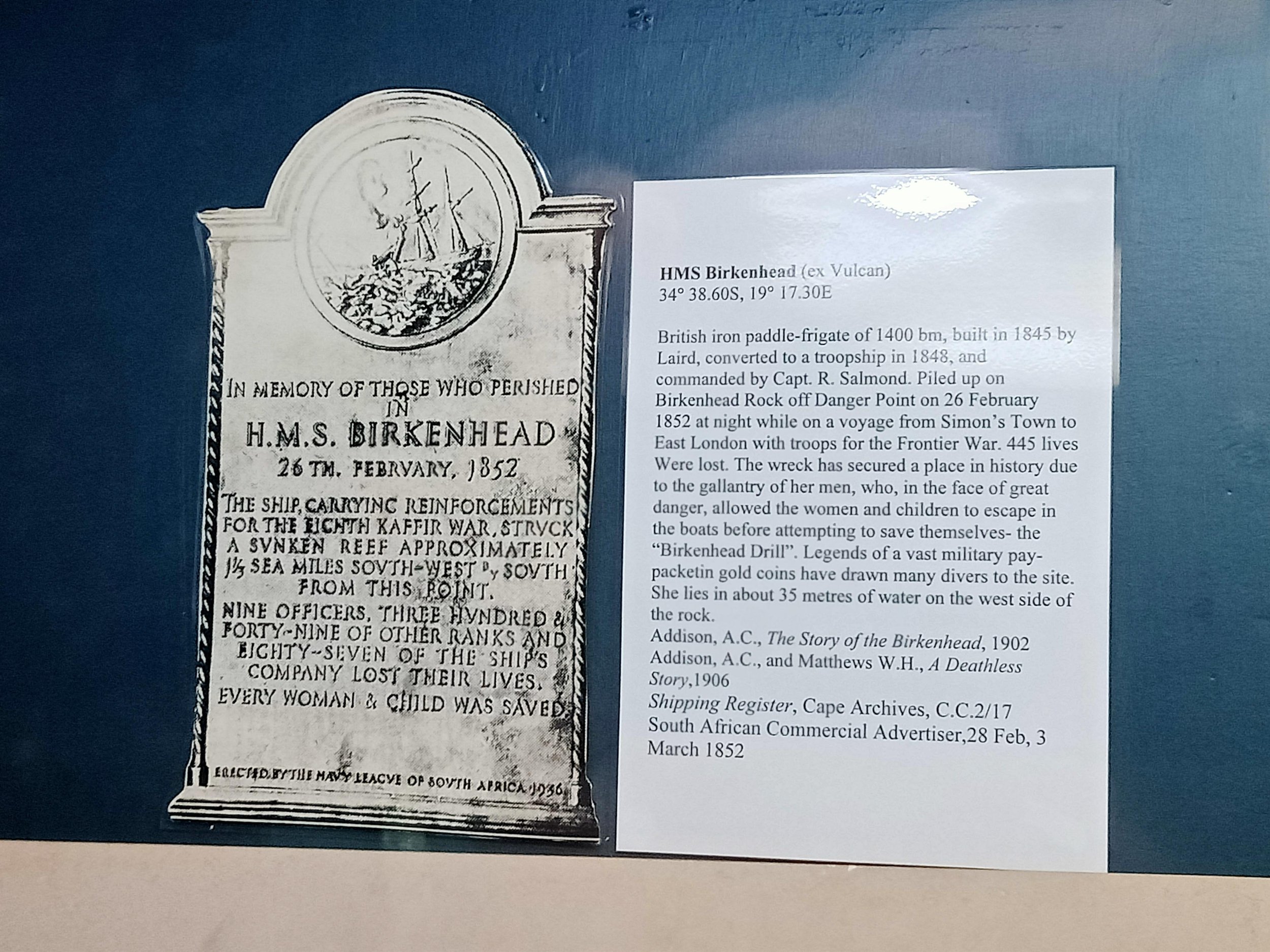

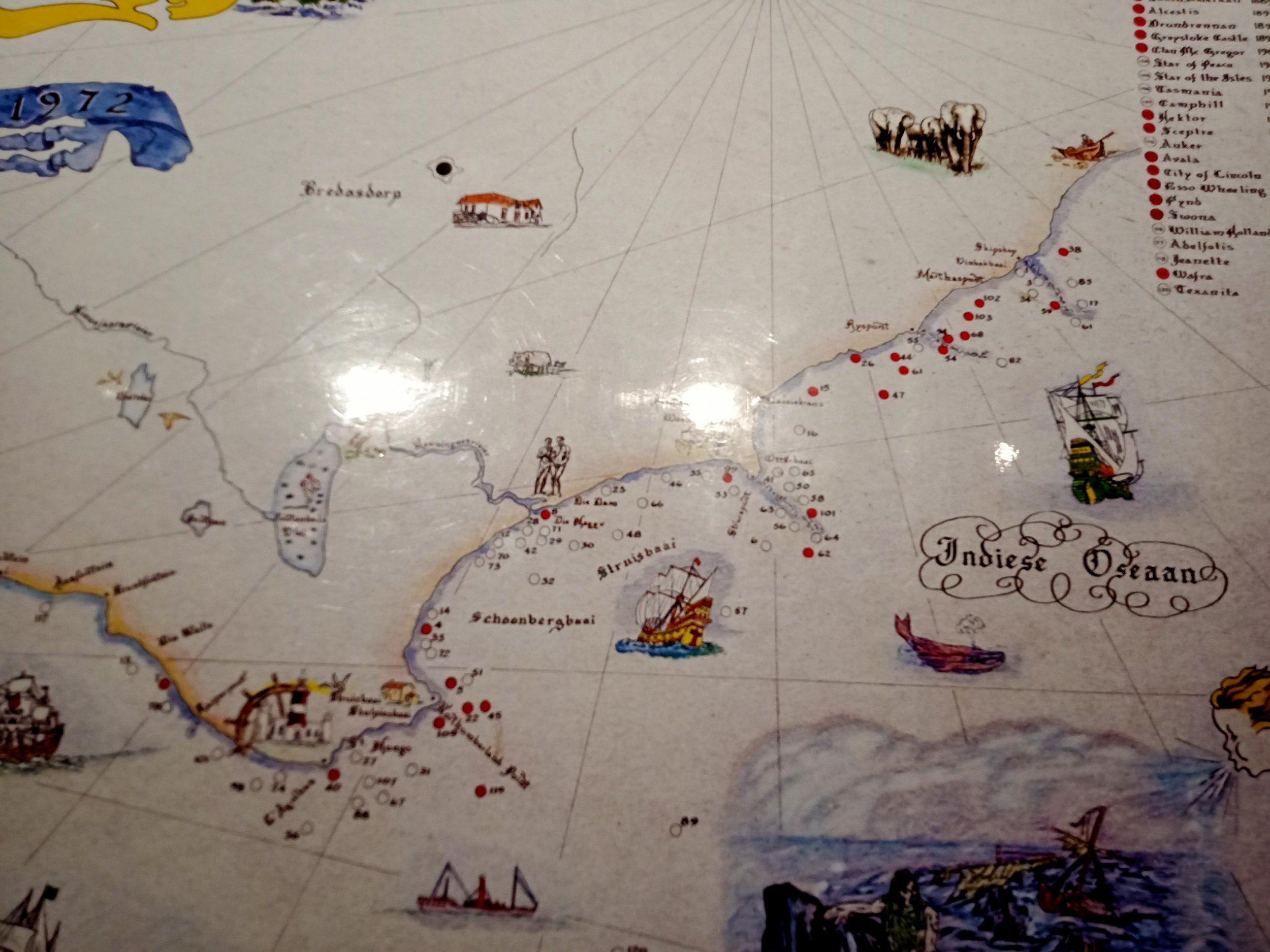

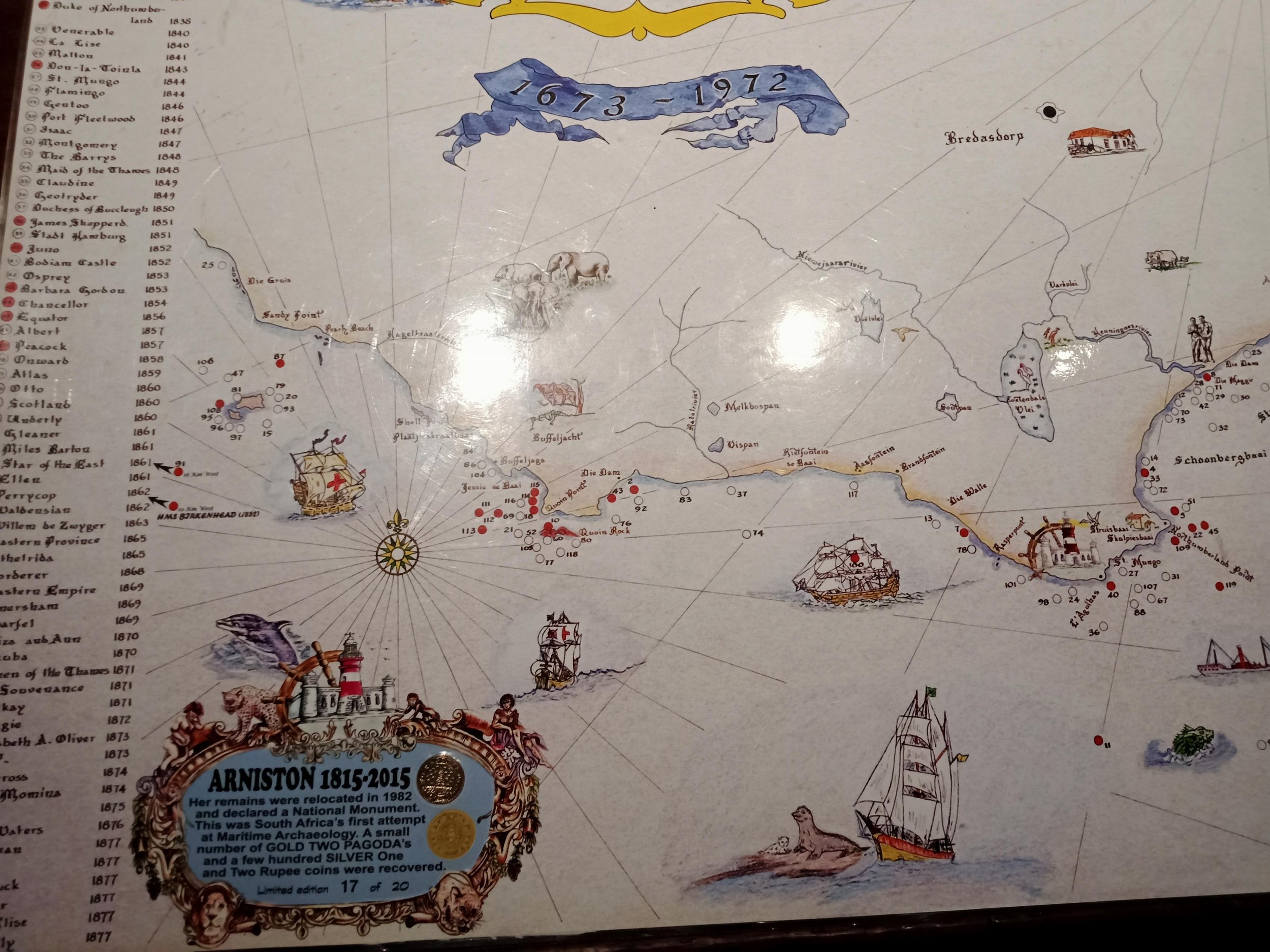

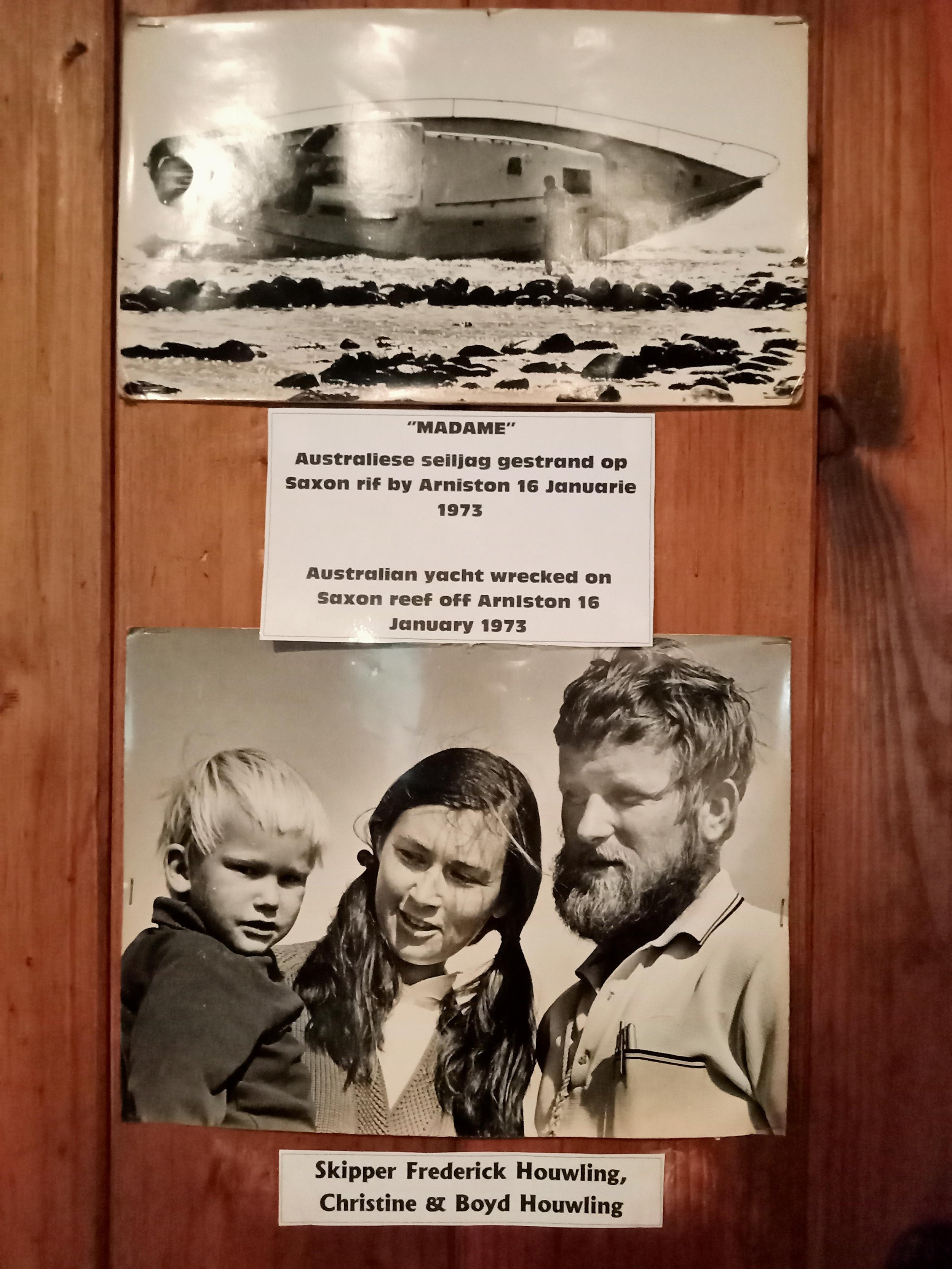

Sailor's milestones are usually chosen as sailors’ milestones because it's not easy to round those marks. Passing Cape Agulhas to exit the Indian Ocean and enter the Atlantic ocean, and rounding the Cape of Good Hope are ocean going marks that have pressured many a sailor throughout all of history. In fact, Cape Agulhas and Cape of Good Hope have competed for years to earn the slot as "the most infamous" cape with the roughest weather in all of South Africa. Sailors of old would debate the topic with fervor, each voting depending on where they most recently wrecked or based on storms they survived but only narrowly escaped. They are both known to be such a pain, there is an entire museum devoted to the wrecks they have caused!

And, so we set off from Knysna knowing the trick is to round these marks while staying afloat, alive, and also married to your sea captain if you happen to be this particular First Mate. Our weather window looked perfect for the feat, and as we emerged into open ocean, the day was calm and bright white, if not sunny, with light pressing down on a continuous grey cloud cover. The ship traffic on this leg was busy, as we crossed what appeared to be a thoroughfare of shipping. We adjusted sails to tie the gaps and slip between what seemed like a steady stream of traffic. “Rush hour!" We said.

Our first day went smoothly, light wind and/or motor sailing until that evening when the wind filled in from behind and we launched the headsail on the pole to hold it out and keep it from flogging as we rolled over swell. It was smooth sailing then on, at least until 3:00 a.m. when all bad things tend to occur.

The Oddgodfrey Disaster of Capes

“Lessssliiieeee, Lesssslliiieee?” The captain leans over me, trying to cajole me awake. I had gone off-watch at 1:30 a.m. to fall dead asleep by two, and he knows I tend to wake up like a lion with a toothache. My eyes split open, then fall shut again as heavy as stage curtains. I groan, “What." I struggle to peel the eyelids apart again.

“The sheet has chafed through and broken, we need to go fix it.” For my non-sailing friends: the “sheet" is the line that leads from the cockpit to the end of the sail, usually keeping it under control and in that nice wing-like shape you imagine sails should be. (I dare not say "rope” as sailing purists will tumble down upon me like linebackers stopping a run to the end zone, protecting the whole world from any hint that there might be "ropes" on a boat. This is a debate for another day, but a rope with a job has its own specific name aboard a sailboat, and cannot then also be called a "rope”. And let the record reflect, I have committed no such sin.) Anyway, this particular rope has parted, sawed away by the jaw of the pole and the constant movement of the sea.

Through the shroud of sleep still wrapped tightly around my head, I can hear the chaos up on deck as the pole hangs loose and the sail is flops and flogs. “Uhggh." Even this bad news is not enough to lift the weight over my eyes, but I know I have to move, so I roll over with eyes still sealed shut to haul my body out of my bunk and stumble over to where my life vest and harness await. I mutter-cuss the universe and its tendency to send all manner of sailing catastrophe only one hour after my off-watch sleep starts. Andrew scurries back on deck to formulate a more cohesive plan.

It's cold. The decks are dewy. There is a full moon, but it is tucked tightly behind clouds. The swell is up, and without the sail to pull us forward, Sonrisa is rolling around like a pig in mud. “Turn on the engine and stop her rolling so much." I say, reaching down to start the motor. I lift my hand to the throttle.

Andrew halts my progress, as he pulls the dead end of the sopping wet line back into the cockpit. The length of it had fallen in the water when it parted, and Andrew didn't think about it until I went to turn on the engine and he could predict all manner of catastrophe having that (rope) wrap itself around Sonrisa's spinning prop.

It Wouldn’t Be a Cape Without a Disaster

With that disaster averted, we edge our way up to the foredeck keeping our handholds the whole way. I capture the wily pole and pull it down while Andrew releases the "topping lift" (also a rope, but not a rope) to lower the pole down to its place on deck. Usually, the solution for this problem is to reach the corner of the sail flopping around, remove the broken piece of line, and then reconnect the end of the still plenty-long genoa sheet (ROPE!) to return to its duties just a few inches shorter. But, one weakness of our high cut sail is that the corner of the sail is very high off deck. At best requires all 6’3” of Andrew and his condor arms to reach it. I try to hold the sail stead with the “lazy sheet” another rope attached to the same sail, but the wind would fill the sail and tug me in whichever direction it liked.

Andrew takes a couple swings at trying to catch it and I grind my teeth knowing that people fall off boats when they are stretching up and over like Andrew was doing. They also get pulled overboard trying to resist the strength of wind like I was doing. "Stop!" I growl, “This is unsafe, you have to stop."

“I can get it!"

“STOOOOPPPPP!"

Andrew is the optimist in the family, but all I can imagine in my head is both of us going over at the same time, each dragging face first in a tangle of harnesses, tethers, as Sonrisa blissfully motored along at her speedy five knots.

"I have my harness on, calm down.”

This does nothing to improve my mood.

But, I’d Rather Avoid A Real Disaster

"Figure out another way. I refuse to participate in this strategy."

We retreat back to the cockpit and stare at our problem.

"I’m going back to bed until we figure this out." I grumble, leaving Andrew to think and Sonrisa to motor along. Its not but a half hour later that Andrew comes to fetch me.

“We have to fix this, the lazy sheet is getting wrapped and tangled on the loose end of the sail.” We repeat the mutter-cussing and I haul myself back on deck. At this point in time, I can't even tell you how this wrap happened. I tried to write about it and just confused myself, so just suffice it to say, the sail was not rolled up tidily as it should be and when we tried to pull it out, we tightened the tangle and caused ourselves more havoc.

The thing about "shipwreck corners" is, it isn't always the weather that takes you down. There are so many potential points of failure: rocks on the coastline, errors of navigation, junk in the water, storms, failures of equipment, and human error. Its never one thing that sinks a boat, usually it is three: one problem you knew about but ignored, one problem that crops up while at sea, and a third problem you didn't know you had. A ship always has known problems to keep up with, and with this fiasco, we were squarely inside the “problem that crops up at sea,” and so we were hoping we could get this particular issue resolved before the "problem we didn't know we had created the overlap of three evils.

Not sure what I would have done if I was a solo sailor without condor arms, but Andrew stretched his full length up while standing on top of the anchor windlass and reached the edge of the sail to yang and flop, pull and tug in various directions until it untied itself from the knot it was in and we were able to unroll the sail a little bit again. Motoring upwind, the sail flogged and flopped across the center of the deck.

“Hey!” Andrew says, easily standing on the cabin top, reaching up and re-tying the line as it was supposed to be as easy as that.

“Oh! Okay, then."

Things So Rarely Go Easier Than Expected

By this time, the sky was lightening to dawn with pinks and purples just kissing the edge of the horizon. Daylight always feels better for me after a struggle through night watch. I retreat below, remove all my dewy clothes and replace them with something warm and dry. I tuck myself in for a few hours of uninterrupted sleep for which I was most grateful.

The whole next day of sailing was pleasingly uneventful, and it was on my watch at midnight we slid across the Cape Agulhas line, crossing from the Indian Ocean into the Atlantic.

“Hazzzah!" I say to Andrew, who only opens one off-watch eye and smiles through his own heavy sleep. “One last ocean to go before we’ve crossed all three!" I marvel to myself as I watch the beam of the Cape Aghulas lighthouse swing in circles and wink “on-off” at me from on shore.

By morning the next day, we were approaching Cape of Good Hope. We were a bit nervous over what could befall us here, some of our friends had experienced 70 knot gusts as they came around this point. But the morning was calm and we slid easily around the Cape as if it were nothing at all. I clicked away with my camera capturing Cape Point socked under fog, our friends the Perrys just behind us, a moment of success in all our sailing stories, “an easy rounding of Cape of Good Hope!” What luck we have!

We thought. Until....